Cornice is relatively easy to install, you just have to take a bit of care and not rush it.

Cornice types, sizes and ceiling heights

Here in Australia it comes in a few different sizes, and several profiles. The standard cheep and cheery cornice is 50mm to a side with a simple cove profile. You can then go up in size to 75mm and 90mm coves.

Then, in the 90mm size you can get a number of different decorative profiles, and each of the manufacturers have their own profiles. The profile we chose is called Sydney, from Boral.

The higher your ceiling, the bigger the cornice you need, otherwise it looks a little odd. Cornice is a feature, so make it work for you – don’t choose a tiny cornice profile for high ceilings. We have 9 foot ceilings (2.7m), and 90mm is the smallest I would recommend for ceilings in the 9 – 10 foot range.

Also, in the grand scheme of things, cornice is not that expensive, so don’t skimp. We paid $4.55 per meter for the Sydney profile from Boral.

Tools & Materials

You don’t need many tools for cornice installation:

- Tape measure and pencil

- Work platform and step ladder

- Miter box and saw (I used a small fine tooth panel saw)

- Plaster mixing tray and spatula

- Measuring cup

Of course you also need the cornice (it comes in 4.2m lengths), and cornice adhesive. I used the powdered adhesive (add water), not the premixed stuff. The powdered adhesive comes in different grades depending on the setting time – I chose the 45 minute grade.

(need picture of adhesive bag)

Step 1 – Markout

Mark out on the wall and ceiling at the corners or ends of the cornice run, some guide lines to help you align the cornice. I am using 90mm cornice, so I cut a bit of wood 90mm wide by 600mm long as a gauge, and marked some guide lines on the wall and ceiling.

If you don’t use gauge lines it very easy to be 5mm out – ie too far down the wall or too far into the ceiling – and that will mess up your corners.

Step 2 – Measure

Measure the cornice length required. Be accurate but don’t sweat about it. Unless your walls and ceilings are exactly 90 degrees to each other, the cornice corners will need a bit of filling, so a few millimetres out wont matter.

Note: I found by trial and error that I really can handle much more than about 8 foot (2.4m) of cornice by myself. I know the pros can, but I dont have the speed to lay out the adhesive and get it up and in position before it starts to set. Also, my work platform is not long enough to allow me to walk along and place more than about 8 foot of cornice in one go. So, for long runs, I just put up with doing joins and getting them as neat as I could.

Step 3 – Cut

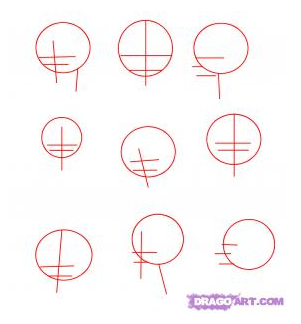

Use your miter box to cut the cornice. Assuming you are dealing with walls that are at right angles, you will need to cut 45 degree miters on all the corners. You will probably have two types of corners – internal and external.

What I did to help me cut the correct angles was make up four bits of scrap cornice with the correct cuts on them – internal left and right hand ends, and external left and right hand ends. It might take you a few goes to get these ‘templates’ the right way around, but when you have, label them, and also label which way around in the miter box they go.

(need photo of 4 templates)

When you cut cornice in the miter box, the ceiling edge of the cornice goes to the bottom of the miter box (ie its upside down). Thats why it pays to label your templates with the edge that faces up when you do the cutting.

I also labeled them with an arrow pointing to where the good side (ie working side) of the workpiece faced, just so I made sure I orientated everything correctly. As a consequence, I did not make a single cutting mistake.

I also found it handy do set up two sawhorses (trestles) with a long (3 meters plus) plank between them. This was my cutting table. I also had a couple of 20mm high blocks to prop the cornice up so it would sit flat in the miter box.

Step 4 – Test fit

Always do a test fit. You will find that you need to shave of a few mm here and there, and you don’t want to do it with glue on the workpiece.

Step 5 – Mix adhesive and lay it out

After some trial and error I found that 225ml of water (I had a plastic drinking cup that was that capacity) mixed with adhesive powder to a thick toothpaste consistency would do about 1.5 meters of cornice (both edges).

Put the water in your mixing tray, and sprinkle the powder in letting the water soak into the powder. The more you mix it, the faster it dries, so if you let the water soak in as you add powder slowly, you have less mixing to do, thus it will give you more working time.

I used a 30mm wide spatula to lay the adhesive onto the cornice in a thick wide bead, covering the flats of the cornice. The pro’s use an 8″ or 10″ plastering knife, but I’m not that good.

I used my cutting plank to sit the cornice on while I glued it up, with the edge of the cornice hanging slightly over the plank edge. Then flip the cornice and do the other edge.

Note: Don’t be a hero and do multiple pieces at once, unless they are quite short. I tried this the first time, and the glue dried before I got to the second piece, so I just wasted a bunch of adhesive.

In general you do waste a bit of adhesive, but thats a small price to pay verses rushing it and having it dry on you before a piece is properly in place.

Step 6 – Put the cornice in place

Orient the cornice the right way around and pick it up, with your arms wide spread and the cornice sitting on your upturned hands – top cornice edge closes to you, and back (glue side) facing upwards.

Walk up your step ladder and onto your work platform.

Put the cornice in place, following your guide lines.

Now just work your way along the cornice pushing it into the wall and ceiling. Keep alternating from end to end to ensure it doesn’t droop off the ceiling. The adhesive will set up relatively fast if you have the consistency right. Make sure its push up to and end or the piece it has to mate with. Pay attention to any joins to get them mating as best as you can. Take care here – you want it looking good.

On the joins I then use my finger to smear adhesive into the gaps, and blend the join.

Now you can use your putty knife to scrape off the excess, and fill in any little gaps between the wall and cornice, and the ceiling and cornice. Be neat here, so there is minimal or no sanding to be done.

Step 7 – Next piece

Return to step one and repeat.

Handling visible ends

Where a cornice end would be visible, you need to cap it with a small external return piece.

This is actually quite easy to do, you just need to take care in the cutting, particularly if you are using decorative cornice, as its easy to tear of the tiny little end of the miter cut.